What is Enterprise Foundations?

Enterprise Foundations – also known as industrial foundations – are foundations, which own companies. The term is not widely known, but many will recognize the names of companies like Bosch, Bertelsmann, Carlsberg, Hershey, Rolex, Investor or Tata Sons, which are owned by foundations or equivalent entities – Stiftungen, Trusts, Fonde, Stichtingen, Fondazioni etc –whose names reflect their legal and national origins.

Read more about Enterprise Foundations in the following sections.

Following Thomsen (2017) and (Kronke, 1988), they are characterized by the following:

- Creation by donation (i.e. an irrevocable separation from the founder)

- Independence (a separate legal personality for the foundation)

- A non-selfish purpose (which goes beyond benefitting the founder)

- A foundation endowment (shares in a company plus liquid financial assets)

- A foundation organization (i.e. a board of directors or trustees, possibly a CEO)

- A foundation charter (the constitution set the founder include goals, governance rules

- Controlling influence (e.g.. voting majority) of a business company

- Subject to supervision (to ensure that the charter and the law are upheld, for example a regulator, to whom the foundation is obligated to submit its annual reports).

An enterprise foundation is created when somebody (the founder) entrusts the foundation with an endowment consisting of ownership rights to a business company. The existence of foundations therefore presupposes a gift, or a renunciation on the part of the donor/founder. This transaction is irreversible. Once given, the founder cannot take it back. Irreversibility separates enterprise foundations from US-style family trusts. By a foundation, we mean an independent self-owned legal entity. Thus, most family trusts would not be foundations in the sense we are interested in here because they can be dissolved and ownership can revert to the beneficial or original owners. However, we consider irrevocable trusts as equivalent to foundations.

The motivations for establishing an enterprise foundation may differ. The owner(s) may want to secure stable ownership for the company. It may be a way to save inheritance and wealth taxes while maintaining control of the company. Or there may be no immediate heirs. There may also be a philanthropic desire to “give back to society”. These objectives can be more or less clearly expressed in the foundation charter (see below).

The foundation is a private (non-government) institution. It has no owners and no members. Enterprise foundations are therefore sometimes referred to as “self-owning institutions”. The irreversibility of the decision to found a foundation is underlined by its effective legal personality. The decisive factor is a clear separation between the personal economic affairs of the founder and those of the foundation. The separation transforms the foundation into a non-profit entity, which, as emphasized by Hansmann (1980, 1987), may make profits but cannot distribute those profits to the organization’s members, directors, officers, or other persons who exercise control over the organization. Moreover, no external party has a claim on profits or control.

Independence here also refers to the independence of the founder and the founding family. In many cases, the founder and founding family are no longer active, so enterprise foundations are not a subset of a family business. Moreover, even if the founding family is still active, it does not exercise unfettered control, but it is bound by the charter and the law. Foundation law may prescribe, for example, that one or more, or even a majority of the foundation board members are independent of the founder.

An enterprise foundation may have philanthropic goals such as donating to charity or running a hospital. Ownership of a business may also be considered an unselfish goal if it benefits customers, employees or other stakeholders, although this is not charitable in the conventional sense of the word. Danish enterprise foundation law distinguishes between the donation goal (charity) and the activity goal (the company). A third kind of non-selfish goal may be a concern for future generations of the founder’s family. So non-selfishness is a broad concept. However, the foundation purpose cannot (solely) be to benefit the founder or his immediate relatives.

Most enterprise foundations engage in both business and charity, for example, they own businesses and use their dividend income for a charitable purpose. There may of course be many kinds of charity. A particularly troublesome kind from a definitional viewpoint is when a foundation supports the commercial activities of a company through donations or cheap loans, which is tantamount to providing a subsidy, and blurs the distinction between commerce and charity. As far as we know, this is rarely the case in normal situations, but many enterprise foundations do come to the assistance of their companies in cases of financial distress (as would many other owners).

In some cases, it is clear that the activities of the business contain charitable, or at least non-profit, elements. This would be the case for a newspaper with the noble aim of informing the general public or ensuring that the views of a particular political party were voiced. As one newspaperman put it, “we make money to sell newspapers, not the other way round”.

Independence presupposes a certain initial wealth, an endowment or at least privileged access to a source of future income (such as the right to future profits from a company owned by the foundation). Once created, however, foundations are in principle self-perpetuating bodies, provided that they are financially viable. In principle, they will continue to carry out the will of the founder for all eternity.

Like other foundations, the enterprise foundation is formally governed by a charter, which defines its purpose and organization. The foundation is obliged to own and manage the company according to the charter, which represents the will of the founder (although behavioural rules are often informal rather than formal). For example, the charter may prescribe that certain worthy causes (such as research, art or charity) should be supported by any revenues beyond those it is considered necessary to reinvest in the business. The foundation charter may also specify that the foundation should act for the benefit of the company, the employees or the national interest. Moreover, the charter may oblige the foundation to maintain majority ownership of the company. The charter may furthermore include specific rules on the composition of the foundation’s board, for example, whether it is self-elective or whether the founder’s descendants are entitled to a seat. Under the constraints set by the charter (which are subject to government approval and supervision), the board acts under its own discretion.

Subject to supervision by government or courts. Foundations cannot be monitored by owners or members. Enterprise foundations are supervised by government offices (e.g. a foundation regulator, a charity commission, courts or the local tax authorities) which monitor whether they are run lawfully and in accordance with their charter (Kronke, 1988). Usually, foundations must submit audited annual reports subject to the same rules as for joint stock companies. These reports may be publicly available or submitted only to the regulator. The foundation regulator may intervene and in extreme cases replace the board in case of neglect or abuse, for example, if the foundation board decides to overpay its own members or to embezzle the foundation by donating to friends and family. However, supervision is limited to “legality issues” (compliance with the law and the foundation charter) and regulators cannot challenge bad business decisions.

Enterprise foundation law differs greatly around the world. Very few countries, like Denmark have codified civil and tax law on the topic. Some – such as until recently the US – have effectively banned them. Others – like Germany – seek to limit foundation involvement in the underlying businesses. The tax treatment of foundations also varies considerably.

So far, we have been defining “foundations”. Now we add the condition that make them “enterprise” – a controlling ownership stake in a business company. The definition is functional. The foundation will be termed “enterprise” whenever it owns a business no matter whether its purpose is wholly charitable. Thus, there is no dichotomy between “enterprise” and “charitable”. Most enterprise foundations are both.

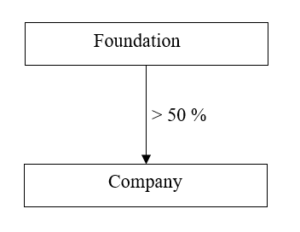

Ownership could be full (100%) or just controlling influence. For clarity, assume that the foundation owns more than 50% of the voting rights. The company will in principle, act like any other joint stock company and be subject to the same company and tax laws.

If a minority of the company’s shares are held by other shareholders―for example, if they are listed on the stock exchange – the company will have a fiduciary duty to all its shareholders and, at the annual general meetings, those shareholders will elect a board to represent their interests. However, as a majority owner, the foundation possesses a controlling influence, which it may (or may not) choose to exercise to elect board members.

Sometimes voting and dividend rights are split which makes for some interesting constellations of foundation and outside ownership. Some foundations retain a voting majority by having the company issue shares with limited voting rights (B shares) to the general public, while the foundation maintains shares with full voting rights (A shares). This is the case in the largest Danish foundation-owned companies Carlsberg, A. P. Møller Mærsk and Novo Nordisk. Another variation is that founding family keeps the voting rights but donates the dividends/cash flow rights to a foundation. This is the case in German Robert Bosch, for example.

Business ownership is what separates enterprise from purely charitable foundations. By business ownership, we mean that the foundation owns the majority of a business company that sells goods and services to the public on a commercial basis (i.e. in a competitive market). We will not be concerned with the exact delimitation of commercial versus charitable activity here, except to say that the commercial activity must be in some sense significant (for example, in terms of magnitude of sales). For example, we will not be concerned with the bookstore or restaurant owned by a non-profit museum unless they develop into sizeable businesses of their own.

Finally, an enterprise foundation is a private institution. Foundations established by government organizations may be considered part of the public sector. Examples could be a museum, a housing agency or a theater, which are set up as independent foundation-owned entities but founded, governed and often financed or otherwise subsidized by the government. The main object will be not to do business but to supply the public with social services at a low price. Quasi-cooperatives or foundations with close links to associations are also excluded. For example, a housing cooperative may legally be owned by a foundation whose board is elected by the tenants, who try to keep rents as low as possible. Or the Federation of Architects may set up a foundation-owned publishing company intended to produce affordable, high quality architecture publications. In both cases, business profitability is a secondary goal.

Although enterprise foundations have been around for more than a century, they have recently attracted attention they as an embodiments of the purpose-driven company advocated by Colin Mayer (2013, 2018, 2019), the British Academy (2019), the World Economic Forum (2020) and others.

Many foundations are non-profits without a personal profit motive, which sets them aside from other ownership structures. Instead, they are legally bound by their purpose, which typically is to secure the longevity and independence of the companies that they own and to contribute to society by philanthropy. As perpetuities which cannot be dissolved, they are long-term owners. However, not all enterprise foundations are equally idealistic. Some have strong ties to the founding family and continue to donate to its descendants. Others again have ties to government organizations, cooperatives or associations, which helped establish them.

British Academy (2018). Reforming business for the 21st century.

British Academy (2019). Principles for purposeful business.

Business Roundtable. 2020. Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation.

https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

Mayer, C. (2013). Firm Commitment: Why the corporation is failing us and how to restore trust in it. Oxford University Press.

Mayer, C. (2018). Prosperity: Better Business Makes the Greater Good. Oxford University Press.

Mayer, C. (2019). Ownership, Agency and Trusteeship (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3522269). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3522269

Thomsen, S. (2017). The Danish industrial foundations. DJØF Publishing.

World Economic Forum. (2020). Davos Manifesto 2020: The Universal Purpose of a Company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Davos Manifesto). World Economic Forum.